Apples in a bag

I only ever taught in Decile 1 or 2 schools. My goal upon leaving Teachers College, as an idealistic 22 year old, was to be the best kaiako I could be for tamariki who often weren't given the best of anything in a system that didn't prioritise them. I knew the difference a vibrant, empathetic teacher could make in the life of a kid who was struggling, I am grateful to have had such a teacher in my Standard 3 year. She saw the potential in all of us and taught us how to believe in ourselves, too. As cheesy as it sounds, this truly made such a difference in my life that year and for many years to follow.

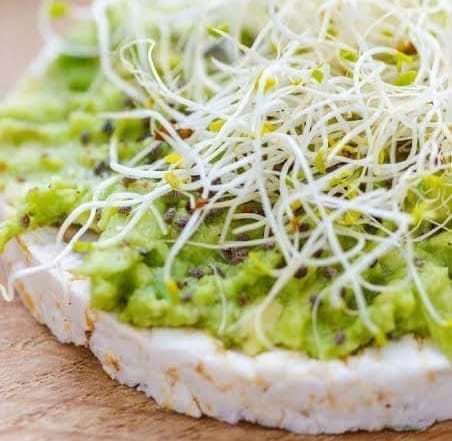

However, my struggles as a 9 year old weren't due to a lack of groceries at home. Oddly enough for a provincial Pākehā kid in the 80s, my lunchbox didn't feature a single fairy bread or jam sandwich, none of that rubbery cheese in plastic, no hard-boiled eggs or saveloys like my classmates. Our family had all sorts of food intolerances, so we were lucky enough to eat gluten-free, sugar-free, or vegan home baking and other experimental delights. I was mocked mercilessly by both teachers and students for years about this 'odd food'. My Click-Clack lunchbox was sometimes kicked around the cloak bay by kids, pulverising the fragile avocado and sprout rice crackers into something resembling a green smoothie. And about as appetising. When I started school, my family lived on my Dad's wages as a mechanic and it was a huge stretch for my parents to buy these ingredients in their efforts to keep us healthy and well. An absolute privilege that I didn't appreciate at all, back then. I just longed for an uncooked packet of 2 Minute Noodles or a cold spaghetti and cheese toasted sandwich with...White Bread (gasp) like everyone else. But I was grateful that I never went hungry.

During my years teaching, I was also a foster caregiver for young teenagers. And my privileged lens on the world was smashed, I soon understood how little tamariki can cope with while they are in survival mode; hungry, thirsty, scared, cold, sleep-deprived, in pain, unsafe, lonely, sick, homesick, heart-broken. A large number of these precious children and rangatahi in my class or home were from refugee backgrounds or had survived abuse and had undiagnosed but likely PTSD. Most of them were learning English as a second or third language and many more had undiagnosed but likely learning or developmental difficulties, neurodivergent needs or vision and hearing impairments that often went unmet. Addressing these complex and layered needs and challenges in the classroom was overwhelming - especially if they hadn't even eaten. I spent mornings comforting tearful children, coaxing others out from under desks, finding lost property to dress them in and responding to concerned and overwhelmed whānau.

I began to see that the first part of the day needed to be spent on connection, enabling everyone to become regulated and ready for learning, play and growth. If there weren't major meltdowns, unexpected visitors or school events scheduled, then the middle part of the day would be filled with all the energetic activity you'd hope to see in a classroom; reading groups, draft writing and maths games, handwriting, crayon and dye artworks, science experiments, waiata, chapter books and so on. After lunch time, our day was unlikely to see much effective learning, despite my best efforts. Too many hours of masking their over-stimulation, suppressing their triggers, speaking in another language, ignoring their hunger pangs and exhaustion and these tamariki would unravel each afternoon. Some would simply fall asleep.

We tried so hard to make sure that they all got something to eat every day. Teachers supervised their students outside each classroom with lunchboxes perched on knees until the '5 minute bell' rang and they dashed off to play. There'd be a 15 minute flurry of sorting out who needed sunscreen, sunhat, rubbish put in the bin, drink bottles and lunchboxes away, getting medicine from the office, new students assigned a buddy and so on. Chaos.

On a good day, there would be 20 minutes remaining for me to speed walk across the school to the staffroom, make a plunger full of coffee to share, go to the wharepaku, heat up leftovers or quickly eat a cheese scone and a mandarin, scull the coffee while chatting with colleagues, rinse my cup, attempt to fit it in the overfull dishwasher and race back to the classroom. This would leave about 5 minutes to get anything ready for the afternoon before the bell rang.

4 out of 5 days each week, this lunchtime dash was punctuated by children with bleeding noses, or who had wet their pants, needed an inhaler, said something mean, wanted a cold pack, started a brawl or had found a delicate blue birds egg to show me. And every single day, there were children brought to the staffroom for a fruit cup and a muesli bar because they didn't have any lunch. Thanks to KidsCan, we could help them out in this small way.

Once the Fruit In Schools programme came in, we could supplement this with seasonal fruit in the mornings and lunchtimes. There were always a couple of tamariki who would linger at the end of the day, hoping to take home any leftover fruit. I started bringing in bags to put any extra fruit aside for them to carry home, knowing that while it wasn't the protein they needed to grow, it was better than them going to bed hungry.

At one school, we had regular donations from Sanitarium and Fonterra; boxes of cereal, bread and milk and it was such a relief to know the tamariki could be fed as needed. Lunchtimes saw teachers buttering toast to give out, left and right. Some tamariki were too whakamā to ask, so we offered breakfast to everyone who was at school early. One child new to my class, started coming in every day at 8.30am, carefully placing Weet-bix into a bowl, pouring over milk and quietly working his way through the kai. He was pretty small for his 7 years and I was shocked to see how many Weet-Bix he was able to put away.

I was 30 years old and had never eaten a single Weet-Bix. The unconventional and disgusting breakfasts of my childhood featured cornmeal porridge, drizzled with lumpy soy milk (made from powder) and flavoured with raisins. However, as an adult able to choose my own breakfast foods, I'd never been tempted to try these dry, dusty slabs of MDF-lookalike that resembled adhesive as soon as milk touched them.

I certainly couldn't fathom how anyone would want to eat 8 of them in one sitting, like this kid did. I wondered if he might have worms and when I mentioned it to a colleague, her face crumpled and she told me his brother in her class was similarly devouring breakfast, fruit and toast at lunch every day. It turned out that the only kai these children had was what they ate at school. My young student was so hungry every morning because he hadn't eaten anything since the bag of leftover apples I'd given him the afternoon before.

Families in Aotearoa are not willingly choosing to starve their children of what they need to thrive, let alone survive. I've never met a parent who planned to deprive their tamariki of kai. Most whānau who are struggling to cover their basic needs are also acutely reluctant to ask for or accept help. The judgement of others becomes a huge barrier to them getting what they need. Patronising saviour attitudes from those who hold power over them further add stigma. They do not need to be blamed for the snowball of challenges they are facing, they need help, kindness, support - and kai. Heaping shame on those in poverty conveniently allows Luxon and other Wealthy White Men like him to divert our attention from the systemic ways in which they benefit from the same decisions that ensure these tamariki are hungry.

Here's a brief overview of how that system plays out;

- May 1839, in England the New Zealand Company (full of Luxonites) starts advertising and selling off whenua in Aotearoa that it doesn't have rights to sell, mostly to European property investors, some who do actually come here to live, 'develop' the land they've got free, or cheaply and become wealthy. Our country's obsession with land ownership and property development as a road to riches becomes entrenched in the dominant Pākehā culture, laws and systems of power. This continues for a bunch of generations.

- Colonisation / Capitalism / Neoliberalism etc

- Fast forward to families who throughout the most intense Covid-19 season have managed to hold onto jobs, homes and keep food on the table. They are relieved when the Lunches in Schools programme is introduced in 2020 and when it proves to be successful, is expanded further.

- In 2023, wealthy people in positions of influence (e.g. landlords) wanting to get richer, donate $$$ to the political parties they believe will bring in policies that benefit their interests. "National led in the value of donations received, totalling $10.4 million – more than double the amount declared by any other party and believed to be the most taken in one year."

- In 2024, Luxon and his coalition government bring in new tax policies for landlords so that they don't have to pay as much tax because it's annoyingly getting in the way of them getting richer. This loss of income to the government costs $2.9 billion that our country can't afford.

- To pay for this, Luxon's coalition government cuts 100s of public sector jobs, cuts staffing in schools and hospitals, cut te reo Māori training programmes...te mea, te mea.

- Cost of living increases exponentially impact those on benefits, Māori and pensioners the most and, shockingly, "highest-spending households" the least. Of course, one of the biggest factors impacting this is rent costs. The very same rent $$$ that are going to those poor landlords who needed a tax break (see 5).

- Meanwhile, the "wealthy and sorted" (i.e. those who own multiple homes, or even 1 home, or who can actually afford rent) sell houses all over the show, some like Luxon make gains of up to 45% each time. You know, thanks to those tax cuts he brought in.

- Grocery prices continue to rise, up a further 2.7% in 2024.

- We see the worst economic downturn for Aotearoa since 1991 (excluding Covid-19). Jobs are cut, wages now don't match the increase in the cost of living and "workers today have lost the bargaining power they used to have when unions were strong and welfare-state thinking prevailed" which means this whole messed up system impacts those with the least financial wellbeing, the most.

- The Lunches In Schools budget is slashed, contracted to an overseas company. These cuts will supposedly save "save $170 million dollars" (you know, to go towards the $2.9 billion needed for the landlords' tax cuts). Jobs are lost by people in the community who had worked for years to hone systems which provided healthy, sizeable, varied, appropriate and tasty kai to kids all over the country. School lunches devolve quickly under the new system; they are not labeled, late, cold, inedible, too spicy, not halal, covered in melted plastic and disgusting. Food wastage is off the charts, schools are trying to deal with rats eating the rotting uneaten lunches.

- Anyone who could barely afford school lunches for their kids in 2020, now is likely to have less well-paid or more unstable work and higher rent. Their food budget has likely adjusted with kids eating at school for 5 years but they're now facing much higher grocery prices right when the school lunches become inedible. New Zealanders spend on average a whopping 13% of our weekly budget on food.

- Instead of taking responsibility for this mess, Luxon has infamously blamed "unhappy parents" claiming they "should take responsibility for feeding their own kids", as being financially secure enough to pay for groceries is not "rocket science". He should be working immediately to sack Seymour, reinstate the funding and local providers for Lunches In Schools and apologies to the children, their families and teaching staff who've had to face this.

Marmite, Weet-Bix or any other Sanitarium product isn't able to address this colonial system which ensures the poor get poorer and the Luxons get Luxier. It's also important to remember that Sanitarium is a registered charity, whose profits go to the Seventh Day Adventist Church and who "partners with Fonterra and the Ministry of Social Development in delivering the KickStart Breakfast Programme, which provides breakfast to 42,000 children each school day." You know, feeding those hungry kids that Luxon says should just be happy with a Marmite sandwich and an apple in a bag.

He states he's "not willing to let them go hungry" - so what is he going to do about it? Luxon is delusional living in the privileged bubble he's built for himself and his cronies.

Kids ARE going hungry. They can't learn, play peaceably or thrive. An apple in a bag doesn't cut it.